Short video clip of the Porvoo Communion (Languaes: Portuguese&English)

News

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2019

The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses.

The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list.

Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week.

In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation.

The Prayer Diary is updated once a year.

For corrections and updates, please contact Revd Johannes Zeiler, Ecumenical Department, Church of Sweden, johannes.zeiler@svenskakyrkan.se.

Download the Porvoo Prayer Diary here:

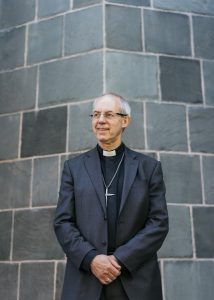

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s sermon at the Porvoo Communion Consultation in Tallinn, oct. 2018

THE LAMBETH AGREEMENT

It is a joy to be with you today and to share in our celebrations of the eightieth anniversary of the Lambeth Agreement between the Church of England and the Evangelical Lutheran Churches of Estonia and Latvia. I bring warm Christian greetings from the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Church he serves. And I bring similar greetings from the Bishop, and Diocese, of Rochester. We hold Estonia, Latvia and their peoples in our hearts and pray this love and faithfulness is shared between our nations. Our churches’ relationship is a fulfilling and deeply meaningful one for us.

The Lambeth Agreement was signed in 1938. It is hard to imagine a darker, more foreboding moment in history. To the east, Stalin’s vicious purges were at their height. These were, at one and the same time, both paranoid and calculated, inflicting physical ruin and emotional pain on the lives of millions, directly or indirectly. I know this only from reading the work of historians. As a community, you have living testimony to this.

To the west, in 1938, a wicked ideology, grounded in ethnic purity, was massing for war and the extermination of Europe’s Jewish population. Terrible, unspeakable things lay ahead, but in our formal agreement, we bore witness to the one, true God who stood above the idolatry manifested from the east and from the west. And we showed there is a common bond and unity in Christ which is not divided by ethnicity, class or any other ideology.

This unity witnessed then and now to the grace and mercy of God. Any society that wishes to reflect God’s character does not victimise those who think, look and act differently to a standard set by the government of the day. Christ died for all and the one who created this unimaginably vast universe cannot be reduced to the status of a tribal god to serve the interests of a ruling power. Neither can he be abolished by organised, militant atheists, whose wishing away of God is about as effective as a child putting their hands over their eyes in the hope that what lies in front of them will disappear.

Those who lived in 1938 read the same scriptures we do, including St Paul’s letter to the Philippians. The imprisoned apostle left his hearers with three recommendations as his epistle drew to a close: rejoice in the Lord; do not worry; and experience the peace of God. Words fall in and out of fashion and in the United Kingdom; rejoicing is one of them. It is reserved for winning wars and royal births. The English would like to use it for winning the football world cup, but that may have to wait to the twenty-second century. Apart from this, it’s not ‘cool’ to rejoice.

But to rejoice in God is to be gripped with his glory and purpose for humanity and for us personally. The God who became human with the sole intention of sacrificing his life for us and breaking the lasting power of death deserves adoration. And in this worship we find ourselves rejoicing. To know the love of God personally is a source of great resilience in life. And this joy should naturally bubble to the surface in us, like the discovery of a new seam of oil.

St Paul then calls on the Philippians not to worry. In the United Kingdom we have a children’s book called Mr Worry. Mr Worry is anxious about everything that happens to him. Nothing can help him to relax. When eventually he is freed from worrying about things, he becomes worried that he has nothing to worry about. There is a lot of truth in this. The anxiety that many people have is not really related to a single issue, and if that issue is solved, it latches onto something else. There is, naturally, a purpose to worry when it emerges. It reminds us we need to do something – perhaps in the first instance to pray. Pain tells us we must act: a hand held too near a flame will quickly tell the brain it needs to move. But when we worry excessively, it is as if we continue to hold the hand over the flame until we are burned.

As St Peter said: ‘cast all your anxiety on him, for he cares for you’. God responds when we unburden ourselves on him. In 1938, people had good cause to be afraid, yet many would have found these scriptures to be a great comfort. As should we. And as we pray for God to relieve our anxieties, we should pay special attention to those whose problems will remain when they have opened their eyes again. At this harvest festival, it does not take much to imagine those communities across our world where the harvest has failed, and hunger lies ahead. This a huge test of strength – and of faith. In Habakkuk, the prophet makes a stunning declaration of faith when he says ‘though…the fields yield no food…yet I will rejoice in the Lord’. Not everyone can summon up such trust, and we owe them our prayers and all who will suffer because of a poor harvest this year.

In the Church of England, the formal blessing at the end of a service uses the words of St Paul, that the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard our hearts and minds. However, the blessing is usually detached from Paul’s wider point, which is that if people want to experience this peace, they should first pray to God with their requests and thanksgivings. This is the transaction God is searching for and it is a peace which anchors us deeply in the life of the Trinity. A community which turns away from God finds its spiritual hunger unsatisfied. The bread of life is discarded, but substitutes must be found to relieve the empty soul. Some of these can be powerfully addictive, like drugs. But there are many medications, like entertainment, shopping and work, which others use to fill the emptiness they feel. There is nothing wrong with these things, but turning to them constantly as a way of filling the void is like trying a diet of fast food. It gives us a boost, but the boost does not last, and we turn back to it again to get another boost, and another, until the diet of fast food ruins our health.

We need this peace, because we never know what lies around the corner. When the fiftieth anniversary of the Lambeth Agreement was celebrated, the year was 1988. The ending of the Soviet Union and Estonia’s restored independence were less than three years away between them. No-one knew that, except the God to whom we offer our prayers. When the seventieth anniversary of the Lambeth Agreement occurred in 2008, it was just as the cracks were forming which led to a global economic crash. Few people predicted this or were clued up to what this would mean.

In 2018, we have more of an idea, as populist politicians emerge, promising to deal with the problems surrounding us. Many flirt with the same ideologies which brought the world to its knees around 1938. We live in the political era of the strong man – and it usually is a man. The modern authoritarian leader is not interested in building up political and civic institutions. They tell people it is easier to place our hopes on one person than to refresh our public life, out of which resilient societies are built. In any case, the strong men across our political world want to extinguish as much civic life as possible, because it is out of a lively community that ideas and opposition emerge.

Only the Lord Jesus Christ has the strength to deliver the people personally. And he did so by submitting himself to weakness and shame on the cross. As St Paul said elsewhere: God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. There are profound lessons for our political life in this.

Who knows what this world will look like when we reach a hundred years in 2038? Of one thing we are sure. The God for whom the nations are but a drop in the bucket will be receiving praise, relieving worry and dispensing peace until his kingdom comes and his will is finally and fully done on earth.

Communiqué from Porvoo Communion Consultation and PCG Meeting in Tallinn, oct. 2018

Porvoo Communion Consultation and Meeting of the Porvoo Contact Group

Minorities and Majorities: A Challenge for Church and Society

Tallinn, Estonia

11-14 October 2018

Communiqué

Representatives of the Churches of the Porvoo Communion gathered in Tallinn, Estonia between 11 and 14 October 2018 for a consultation entitled ‘Minorities and Majorities: A Challenge for Church and Society’. The consultation took place at the Theological Institute of the Estonian Lutheran Church where we were made welcome by the Dean, the Reverend Professor Dr Randar Tasmuth. The relationship of communion between our churches was grounded and made visible in our gathering together for prayer and our celebration together of the sacrament of the Eucharist. In study of the scriptures we sought together the word of God for each of us and our communities.

Our churches and people exist in and serve complex societies. Within our societies and churches there are minorities and there are majorities. Sometimes an individual can be part of a majority group and a minority group at the same time. In some of our societies our churches form a majority, in others a tiny minority. In all our churches we seek to be open to all: recognising the sins of prejudice that cause people to fear or reject those who are different from them.

During the consultation we heard and reflected on stories of the personal experience and the reality of the lives of minorities;

We heard some of the history of those minorities which were created by war or shifting national boundaries and we reflected on the deep memories of enmity and prejudice that linger as a result of this history;

We learned about the growth of minority communities brought about by immigration; their positive and negative experiences; and those of the majority communities alongside which they live;

We heard about communities that had been in a majority but which, in the modern age, are coming to terms with now being effectively a minority.

In all these examples there is a question for the churches to which we belong as to whether they support the status quo or seek to be counter-cultural in their context.

All of our learning was grounded in the reality of Estonia with its modern history of external influence, occupation and independence. We were privileged to hear from local Church leaders about the life and growth of the churches in Estonia. We were inspired by the example of creative co-operation between the Church leaders. The solidarity that grew among the churches in Soviet times is being sustained in the present day and is bearing fruit.

Representatives from the churches of the Porvoo Communion, spread across the Nordic and Baltic States, the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula and beyond learned from one another. At the heart of our learning was the deepening conviction that God who made humankind in his image loves each person he has made and calls us as individuals, as churches, and as societies to reflect that love and to see the person of Christ in our neighbour.

The consultation concluded in the celebration of the Eucharist at Tallinn Cathedral where the president was the Archbishop of Estonia, the Most Reverend Urmas Viilma, and the preacher was the Bishop of Tonbridge, the Right Reverend Simon Burton-Jones. At this service we commemorated the eightieth anniversary of the agreements of intercommunion between the Church of England and the Evangelical-Lutheran Churches of Estonia and Latvia. These agreements form part of the tapestry of agreements between our churches that predated and prefigured the Porvoo Agreement.

The Porvoo Contact Group expresses its gratitude to the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church, to Archbishop Viilma and to the Reverend Tauno Teder and Ms Kadri Pöder for making members so welcome in their beautiful city. This meeting was also the last meeting for the Lutheran Co-Chair, Bishop Peter Skov-Jakobsen, who completes his term of office with the gratitude of all who have worked with him. The Group looks towards its next conference, in 2019 in Portugal at the invitation of the Lusitanian Church, where the topic will be the voice of the Church in the public square.

Participants

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark

The Revd Christa Hansen

The Revd Dr Thorsten Rørbæk

The Rt Revd Peter Skov-Jakobsen, Lutheran Co-Chair

Church of England

The Revd Dr William Adam, Anglican Co-Secretary

The Revd April Almaas

The Rt Revd Simon Burton-Jones

The Ven Karen Lund

Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church

Ms Kadri Eliisabet Pöder

The Revd Tauno Teder

Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

The Revd Dr Tomi Karttunen

The Revd Dr Niilo Pesonen

The Revd Dr Hannele Päiviö

The Lutheran Church of Great Britain

The Rt Revd Dr Martin Lind

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland

The Revd Dr Sigurður Arni Þórðarson

Church of Ireland

The Revd Suzanne Cousins

The Most Revd Dr Michael Jackson, Anglican Co-Chair

Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia

The Very Revd Elijs Godiņš

Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church Abroad

The Very Revd Dr Andris Abakuks

The Most Revd Lauma Zušēvica

The Very Revd Kārlis Žols

Church of Norway

Ms Beate Fagerli

The Revd Steinar Ims

Lusitanian Catholic Apostolic Evangelical Church – Anglican Communion

The Rt Revd Dr Jorge Pina Cabral

Mr José Serafim Filipe Sequeira

Scottish Episcopal Church

The Revd Dr Hamilton Inbadas

Ms Miriam Weibye

Spanish Episcopal Reformed Church

Mr Ruben Baidez

The Rt Revd Carlos López Lozano

Church of Sweden

The Revd Andreas Holmberg

Church in Wales

The Revd Dr Ainsley Griffiths

Prayer Cycle 30 april 2017

Church of Sweden: Diocese of Gothenburg, Bishop Per Eckerdal

Scottish Episcopal Church: Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway, Bishop Gregor Duncan

Prayer Cycle 2 April, 2017

Church of Ireland: Diocese of Armagh, Archbishop Richard Clarke

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Funen, Bishop Tine Lindhardt

Prayer Cycle 26 March, 2017

Church of Sweden: Diocese of Lund, Bishop Johan Tyrberg

Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cashel, Ossory and Ferns, Bishop Michael Burrows

Church of England: Diocese of Ely, Bishop Stephen Conway, Bishop David Thomson.

Communiqué from Porvoo consultation on Identity, memory and hope

THE PORVOO COMMUNION OF CHURCHES

Communiqué

From the Porvoo consultation on Identity, memory and hope: the continuing significance of reformations for our churches and societies.

Around 30 participants from 11 different Lutheran and Anglican churches met in Bergen, Norway, February 25 – 28, 2017 for a consultation of the Porvoo Communion of Churches. They gathered to reflect on the 500th anniversary year of the beginning of the Reformation, particularly timely in a world where churches are challenged to respond in love and peace to assert once more the message of hope in a troubled and troubling world. How we tell the history of the Reformation continues to shape the identity of our churches and our societies. The consultation considered some examples of that process and explored how fresh ways of remembering the past can open up new and hopeful ways of imagining the future, for our churches and our societies. The conference was co-hosted by the Anglican Chaplaincy in Norway and Church of Norway.

Around 30 participants from 11 different Lutheran and Anglican churches met in Bergen, Norway, February 25 – 28, 2017 for a consultation of the Porvoo Communion of Churches. They gathered to reflect on the 500th anniversary year of the beginning of the Reformation, particularly timely in a world where churches are challenged to respond in love and peace to assert once more the message of hope in a troubled and troubling world. How we tell the history of the Reformation continues to shape the identity of our churches and our societies. The consultation considered some examples of that process and explored how fresh ways of remembering the past can open up new and hopeful ways of imagining the future, for our churches and our societies. The conference was co-hosted by the Anglican Chaplaincy in Norway and Church of Norway.

The opening presentation of the consultation from Revd Canon Dr Charlotte Methuen from the Scottish Episcopal Church explained the formation of new ‘confessional’ identities in Western Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and how they brought together a range of different factors from doctrine and liturgy to the layout of church buildings and methods of church administration. The linkage in some places between confessional and emerging national identities was noted, and in discussion participants explored how far these identities remained influential today, and how far they had weakened or been eclipsed by other forces shaping contemporary self-understanding.

Martin Luther is the decisive figure in the origin of the Reformation, so what is his continuing legacy for Christians today – not only Lutherans, but also Anglicans and more widely in other traditions? Revd Anne Burghardt, who is coordinating the anniversary activities and resources offered by the Lutheran World Federation, argued that there are two particular aspects of Luther’s work that have enduring significance for all the churches. The first is his understanding of God’s liberating grace: the good news of God’s unconditional love sets us free from self-absorption and the need to make ourselves worthy, so that we can seek the will of God and serve one another joyfully in love. The second aspect is Luther’s determination to make the word of God in Scripture available to all and his deep commitment to the educational work required for that to be a reality. Also, the translation of the Bible and the use of the vernacular in the liturgy enabled and accelerated the development of individual national languages. This theme has powerful resonance in societies where education is being geared more and more tightly to narrowly economic objectives, for the student who receives it and the society that support it.

Is the reform of the church something that only belongs to the past? The Revd Canon Dr Jeremy Worthen from the Church of England described four different phases in how reform has been understood in Western European Christianity. Commenting on the way that in the past century and a half, it has become a common term in more or less secular contexts, he proposed that churches needed to take care to ensure that their approach to reform was shaped by a theological framework drawing on the rich traditions we share in this area. Responses from participants indicated that reform indeed remains a widely influential category for many of the member churches of the Porvoo Communion, but also one that is bound up with forms of institutional change that may be controversial or resented. To what extent is our contemporary experience of church reform one that speaks of God’s liberating grace?

When describing the good news they have to share, Christians characteristically speak of salvation, and it was over the meaning of salvation that Luther challenged so sharply the church leaders and teachers of his own time. But what might it mean in our contemporary societies to speak of the good news of salvation? What is it that we wish to be saved from? How may salvation be conceptualised beyond a Christian framework and how might interreligious connections contribute to the healing of the nations? A further question was raised: do we need to redefine sin as well as salvation? Prof Dr Marion Grau from the Norwegian School of Theology listed some of the ‘signs of the times’ for member churches of the Porvoo Communion, proposing that in order to respond they would need to draw on the full breadth of models and metaphors for understanding salvation in Christian tradition, including approaches that have been neglected or that arise from dialogue with new partners for the churches. Identity is flexible, rather than essentialist. Such an understanding of identity opens you up to engagement with the other who is already your neighbour.

The challenges that the churches are facing today were presented through four case studies. These, in addition to group work and exchange among participants, as well as related material, contributed to a consultation raising a rich range of themes from many contexts. Some of the insights shared were:

· How we receive our neighbour today

An important part of receiving our neighbour is the way we welcome strangers. A pressing issue is how we accommodate migrants in our societies, by including them into our church communities, or providing space for worship, and space for sharing. To be true to the reformation understanding of God’s Grace, we need to be open to what others can provide us with. Openness to receive gifts from strangers, neighbours and migrants is challenging, in that we might have to learn anew, and to change our ways and habits. However, if we as church are not open to change our ways, the changing society we live in will not be able to relate seriously to the church.

· The use of language

We live in a time where the very concept of truth is questioned, and where people can refer to an individualized truth, or faith. In this context we need a faith language that can be understood in a wider society. This does not entail losing our inherited faith language, but challenges our habit of speaking a church language that may distance us from people seeking our community. Re-imagining the way we communicate, may be an enrichment to the way we express our faith in action. Finally, we must remember that hospitality implies listening and an invitation to active participation, as well as openness to the need for quiet participation.

· Consciousness about our privileged situation

Our churches live in welfare states. This entails the danger of becoming passive in more than one way. On the one hand, it is uncomfortable to face a potential situation where privileges might be taken away. It may be easier to conform to a religious majority situation where it suffices to culturally belong to the majority religion, even if it is being used to support nationalism and xenophobia.

On the other hand, even if we as churches want to be interactive and inclusive, a privileged situation might easily make us forget our own need for help and input. In turn, this may cause mistakes in our analysis of the situation of others. It may also cause us to actively organise people into groups in need instead of being truly inclusive to people. Finally, to overlook our own privileged situation, may make our message of hope irrelevant.

· Communicating a message of hope and community

How do we speak of faith and salvation today? This is not a question of giving up the core message of our Christian hope, although people may reject it. It is about allowing our neighbour to express what his or her own hopes are. If we revisit the richness of our own Christian tradition, we may find answers to the question of how we convey hope to people today. As the passion story of suffering and pain may respond to the suffering of people today, the Easter message of resurrection and new creation may convey hope. In the wealth of our tradition´s imagery we may find images that can be understood and perceived today. In a similar way, the concept of God´s gift of grace, as it was revisited throughout the reformation, may today respond to the inherited guilt, which for some people today leads to self-destruction or aggression. The church must convey the message of God´s grace with care in a time of individualism, as grace is not a personal possession. The grace of God can be received in faith, but is not a matter of individual achievement. God´s grace is a gift. This challenges our churches to be communities of faith and hope where this gift can be experienced.

The local contexts in which we worshipped contributed significantly to the consultation. The Sunday Eucharist was celebrated in the Bergen Cathedral, and the Opening and Closing worships, as well as morning and evening prayers, were held at St. Mary´s Church, where we witnessed the partnership in mission between the Anglican chaplaincy in Norway and Church of Norway in Bergen. We also received and enjoyed the hospitality and companionship of the local church communities, and Bjørgvin diocese of the Church of Norway. In the midst of its surrounding nature, the interaction of art, history, religion and commerce in contemporary Bergen, was brought together in a walking tour led by the artist and philosopher, Mr Arne Magnar Rygg. The tour provided an opportunity to use many senses in perceiving what identity means, locally, and historically.

The Porvoo Communion of Churches is the result of an ecumenical agreement that brought together a wide range of Anglican and Lutheran Churches who have been sharing a common life in mission and service for the past 21 years. The vision of the Porvoo Common Statement is to be together in mission and ministry. Churches in Europe continue to seek membership of and to join Porvoo today.